|

The principal challenge of environmental mainstreaming is to improve governance. Mainstream institutions such as treasuries, planning departments and corporations have not generally recognised the environmental underpinnings of development. They treat the environment as a ‘free’ good, and environmental damage as having minimal cost. Thus the environment tends to be unvalued, unpriced, unmonitored, and left on the margins of major institutions and their decisions. Although most governments have signed up to a range of international agreements to preserve (global) environmental values, prevailing governance frameworks are not set up to treat these as a priority.

Environmental mainstreaming is, therefore, a long-term societal/institutional change endeavour that entails bringing together a new set of systems and a set of associated values, rules, norms, procedures and other tools that works for specific contexts – a governance challenge. That challenge does include issues of data, information, skills and resources that are commonly addressed by environmental mainstreaming ‘projects’. But, more fundamentally, it encompasses values, beliefs and decision-making frameworks that are not so easily dealt with unless the ‘mainstreaming’ endeavour is clearly set up as an institutional development approach. That takes real leadership and careful tailoring to the local institutional context. Environmental mainstreaming also needs to aim purposefully to change the way organisations and people view the environment and hence behave – something that can be approached, for example, through environmental education or induced as a response to catastrophies. Furthermore, environmental mainstreaming needs to be achieved at a range of scales in relation to time, geographic impact, actors/institutions involved and even financial considerations (see Box 5.1).

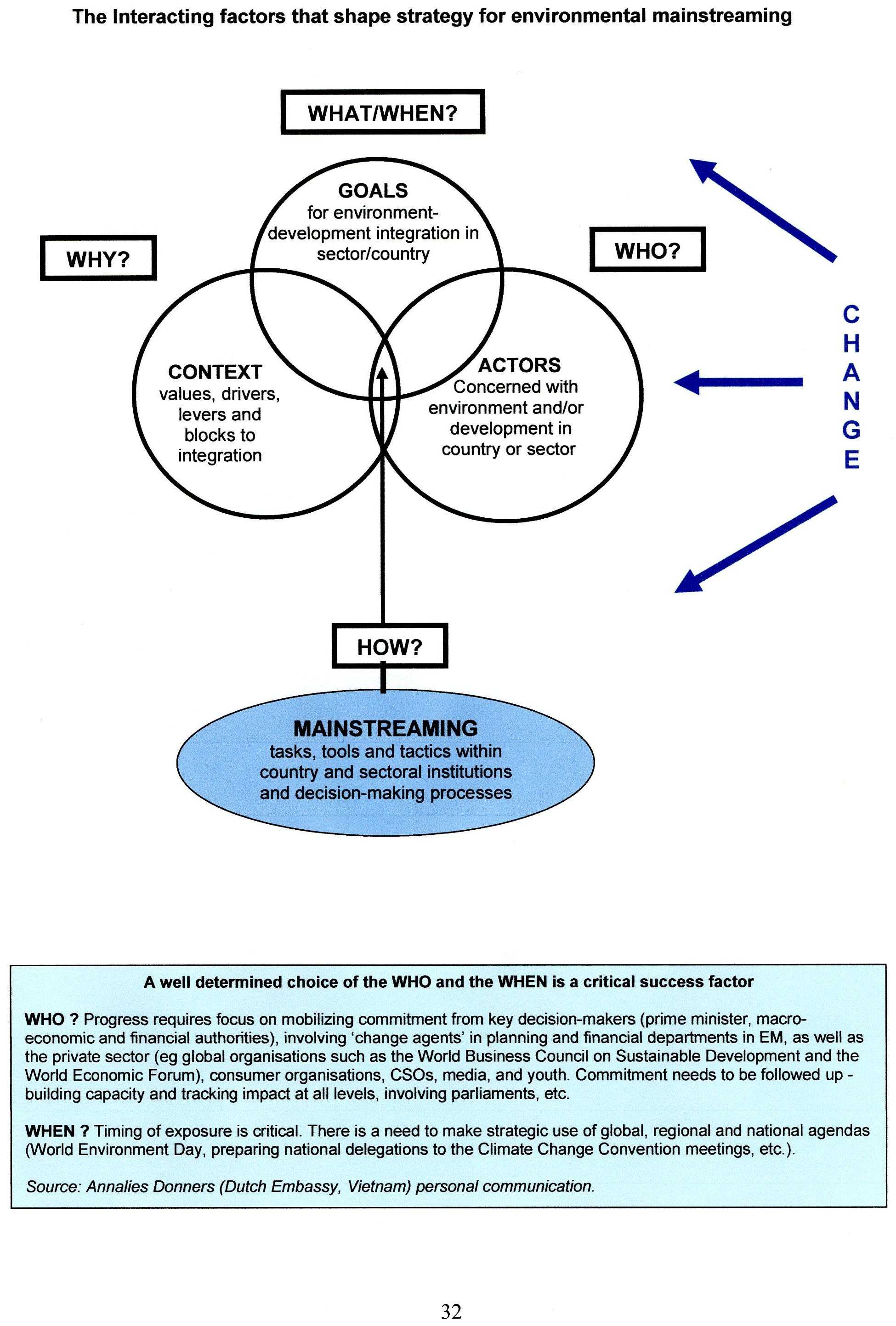

Work by IIED in 2007-08 involved a range of country ‘surveys’ which focused on country contexts and their range of entry points and drivers. The surveys picked up on stakeholder perspectives from those who regularly have needed to use, or commission others to use, environmental mainstreaming tools/tactics. These surveys highlighted the generic complexities of mainstreaming, i.e. its multi-issue, multi-layer, context-specific nature. They revealed that the need to tailor approaches to the country context, to be clear on the specific mainstreaming goal, or to involve the right actor are just as important for mainstreaming, perhaps more so in some circumstances, as issues concerning the choice of a precise tool . Figure 5.1 presents a framework/platform for describing these dimensions.

Box 5.1: Scale dimensions of environmental mainstreaming

Environmental mainstreaming (EM) interventions could be focused in relation to various aspects of scale:

Temporal scale: EM could take place over a range of time periods, from a single day used to raise an issue, to a decade-long campaign. Similarly the benefits of EM could be experienced over varying time scales.

Geographic scale: EM can be undertaken in a range of physical spaces, e.g. in a very small geographic area, such as an individual farm or community, across a district or entire country, or in an ecosystem or bioregion.

Institutional scale: EM may involve actors (organisations and individuals) at different levels from very local to international - for example: local community resource users; government, the business sector and NGOs at national, sub-national and local levels; and international (e.g. UN) organisations, parties to multi-lateral environmental agreements and global financial market actors.

Financial scale: EM can be promoted in various ways, e.g. through projects with dedicated budgets of varying sizes; financing mechanisms such as the clean development mechanism (CDM), carbon trading, REDD, etc.; or through the regular operations of international organisations, government ministries/agencies or other actors such as NGOs, landowners or private sector companies.

Source: adapted from Petersen and Huntley (2005) |

Figure 5.1: Interacting factors that shape strategy for environmental mainstreaming

|